by Stuart Penney

Sometime during 1971 I answered an advertisement in the London Evening Standard for a casual job as a house and flat cleaner. It certainly wasn’t the kind of employment I would normally undertake but I was, how shall I put it, “resting” at the time. That is to say, I was signing on at the Labour Exchange and sponging off my girlfriend while simultaneously pursuing an increasingly unpromising career as a musician. With the UK unemployment figures sitting at a low 2.5% and jobs plentiful, the DHSS (Department of Health and Social Security, as it was then) took an understandably dim view of long-term benefit claimants, so urgent measures were called for before the dole cheques dried up.

The advert made the job sound almost attractive. It promised flexible hours, implying you could choose to work only when it suited, thus avoiding those tiresome early morning starts, which I thought seemed perfect. How wrong I was. For a start, the pay was beyond pitiful, even for the time. The workers received a paltry £1.50 per cleaning job, out of which we gave 50p commission to the agency. And you really couldn’t do more than two jobs a day, even if you had the inclination, or the stamina, since you had to find your own way to each location by bus or tube and pay all travel expenses yourself. Plus, the bookings were often in far flung suburbs of London, involving huge travel time and plenty of walking.

The cleaning agency’s HQ was a seedy office above a Carnaby Street boutique and there always seemed to be a number of oddball characters coming and going, lending the place an air of danger. On my second visit there I encountered infamous black power activist Michael X (1933-1975) furiously berating another man on the stairs over an apparent late delivery (of what I never discovered) and I began to suspect the agency might possibly be a front for something other than house cleaning.

I never quite figured out the extent of his connection with the company, but Michael X (real name Michael de Freitas, aka Abdul Malik) was often seen hanging around the office, acting like he owned the place and silently glowering at anyone who dared pass the time of day with him. Why the self-styled "most powerful black man in Europe" was involved with a down-at-heel cleaning agency was unclear. He certainly wasn’t cleaning houses, that’s for sure. Despite a somewhat murky past, which included working as an enforcer for notorious slum landlord Peter Rachman and serving jail time for stirring up racial hatred, he had, paradoxically, become the darling of London’s left-wing counterculture and stories of his exploits regularly appeared in the underground press, including International Times and Oz magazine.

In 1967 he hooked up with Swinging London scene maker and UFO club co-founder John “Hoppy” Hopkins (1937-2015) and was instrumental in organising the first outdoor Notting Hill Carnival. He eventually entered John & Yoko’s orbit and after the couple famously shaved off their flowing locks for charity in early 1970, they donated a bag of their hair to be auctioned in aid of one of Michael’s revolutionary causes. The Lennons were going through their pro-active political phase at that time and so were ripe candidates for the kind of radical sloganeering Michael X and his unsavory acolytes were espousing. John & Yoko's largesse even extended to paying Michael's bail when, along with four others, he was arrested for extortion in 1971. A month later he skipped the country with unseemly haste.

The man who ran the agency, a smooth-talking Arthur Daley type, told me he had been the manager of Liverpool band the Koobas and while his claim seemed a little random, as I believe the younger generation say, I had no reason to doubt that he was telling the truth (although, to be fair, he looked nothing like Tony Stratton Smith or Brian Epstein, both of whom claimed to manage them). The group never made the big time, and few would have heard of them - then or now - so why bother to invent such a tale? To add to his claim, a copy of the Koobas’ LP sat permanently propped up on a bookcase behind his desk and he always seemed keen to talk about the band who had supported the Beatles in 1965 and Jimi Hendrix in 1967 but had broken up before their sole album was released. Now unfeasibly rare, original pressings of that self-titled Koobas record regularly sell online for more than £1,000 today, despite being reissued several times along with their entire recorded output on retrospective labels such as The Beat Goes On.

The cleaning jobs were often in respectable middle class London suburbs such as Mill Hill, Hendon and Golders Green out on the far reaches of the Northern Line, and involved plenty of tedious silver polishing, dusting and vacuuming for bored Jewish housewives (not a euphemism) who were endlessly fussy and seldom happy with my standard of work. During that period, I must have taken the Brasso (or was it Dura-glit?) to dozens of menorahs (that's seven-branched Hebrew candelabrum to you) the sacred religious symbol found in so many homes in that part of North West London. I was new to all this, and it was a window into a strange and unfamiliar world.

But now and then something more interesting would crop up. One day I was sent to an upmarket penthouse on the top floor of a tall apartment block near Victoria Station. It transpired that the beautifully furnished luxury flat belonged to the American record producer and songwriter Kenny Young (1941-2020). He’d co-composed several famous songs including “Under the Boardwalk” a huge 1964 hit for the Drifters (also recorded the same year by the Rolling Stones on their second LP).

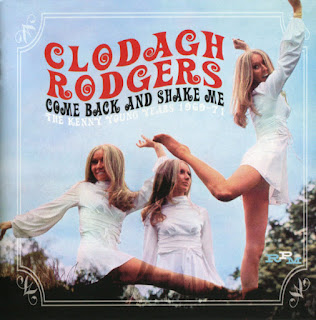

Young's song "Gentleman Joe's Sidewalk Cafe" was covered in 1968 by Status Quo on the B-side of their first hit "Pictures Of Matchstick Men." Born Shalom Giskam in Jerusalem, he moved to New York as a child and, after changing his name to Kenny Young, took a job as a songwriter at the famous Brill Building in 1963. Although not successful in the US, a recording of his 1968 song "Captain of Your Ship" by Reparata & the Delrons became a UK hit so Young came to Britain with the band to appear on Top of the Pops. In 1969 he took up residency in London and began working with Irish singer Clodagh Rodgers for whom he wrote, arranged, and produced a string of UK pop hits, including "Come Back and Shake Me" probably her biggest seller, reaching #3 in the singles chart.

Although not conventionally handsome pop star material himself - he was a tall, ungainly man with oversized, owlish glasses - Young released a couple of early 70s solo albums on Warner Brothers: Clever Dogs Chase the Sun (1971) and Last Stage for Silver World (1973) before forming the band Fox with Australian singer Noosha Fox in 1974. They scored a trio of mid-70s hit singles including "S-S-S-Single Bed" which reached #4 in the UK and topped the Australian charts.Kenny was not at home when I arrived, but a stunningly attractive lady who I presumed was his wife buzzed me in via the intercom. She was laid up in bed with a box of tissues and a streaming cold but directed me to the kitchen where, to my surprise, I found a large and quite magnificent Afghan Hound. You rarely see them today, but during the 60s and 70s Afghans were the default fashion accessory dog of choice for rock stars, media celebrities and King's Road poseurs alike.

The scene which greeted me in the kitchen was a sight to behold. It seemed the dog had been confined to the apartment for some considerable time because it had relieved itself on almost every square inch of the kitchen floor and the smell was overpowering. I was told where the disinfectant, sponges, mops and buckets were kept and instructed to clean up after the animal, a task which seemed, at the time, no less unpleasant and insurmountable than the fifth labour of Hercules (those lacking a classical education may care to look this up). Next, I was expected to wash what appeared to be a week's worth of dirty pans and dishes. All of this was done without the aid of a single pair of Marigolds, I should add.

When I'd completed these soul-destroying tasks, Kenny’s wife asked if I wouldn't mind feeding the Afghan (fresh meat only, of course, not tinned) before taking it down to street level and walking it around the block for a while, in the hope of forestalling a repeat performance of the kitchen soiling incident. Luckily, I love dogs, so it was a welcome break from the tedium of cleaning and, after the gag-inducing smell in the kitchen, I really needed a breath of fresh air at that point.

But Victoria is a very busy place at the best of times, and this was rush hour. The huge dog, though docile with a lovely temperament, was highly strung and nervous in traffic. It proved a real handful, straining on the leash every time the whoosh of air brakes from a passing bus or truck was heard, and I was worried it might dash into the road, possibly taking me with it. So I made absolutely sure to keep a tight hold of the valuable animal.

After the Afghan had done the business on a quiet side street, we took the lift back to the penthouse to find that Kenny had arrived home in the meantime. He was shocked and embarrassed to find I’d had to clean up after his dog and couldn't apologise enough. He even slipped me an extra ten-pound note as I left. That was more than I’d earned for the entire week. What a gentleman!

I didn’t last much longer at the cleaning agency after that. It was menial and unrewarding work and, as a guitarist, I had to take care of my hands, after all. But to this day, whenever one of those poptastic hits by Clodagh Rodgers or Fox comes on the radio, I still associate it with Kenny Young, a certain skittish Afghan Hound and, with due acknowledgment to Derek and Clive, the absolute worst job I ever had.

As for Michael X, in the mid-70s he went on trial for a double murder in his native Trinidad. Yet again the Lennons stepped up and paid for his defence lawyer, the controversial civil rights activist William Kunstler. But it was to no avail. Michael was found guilty and hanged in Port of Spain jail on May 16, 1975, aged 41. Not for the first time had John & Yoko’s patronage proved somewhat ill-advised.

Trivia Footnote: As mentioned above, during several brief periods of unemployment I had to report to the Labour Exchange, as they were then called (they were renamed Job Centres in 1973) once a week to confirm I had been actively looking for work. Like most things I believe it's all done online today, but back then "signing on" as it was known, involved a face-to-face grilling from a soulless civil servant in an equally grim and soulless government building. It wasn't always a bad experience, though. At my local dole office in North West London I sometimes found myself queuing behind the actor Frank Richards (1931-2022) who played effete vicar the Reverend Timothy Farthing in the much-loved BBC TV series Dad's Army. This was always a minor thrill which cheered up an otherwise depressing experience no end. Like myself, Frank was presumably also "resting" between engagements in 1971.

.jpg)