by Stuart Penney

I probably won’t be buying the inelegantly named The Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments - Time Out Of Mind Sessions (1996-1997), due for release this month. I’m writing this in February 2023, and it seems my almost 60-year love affair with the music of Bob Dylan is drawing to an end. Sorry, Bob, it’s not you, it’s me. But with each passing year and every new album the relationship is getting harder to maintain. Disclaimer: in reality the title of this piece should probably be something more mundane and less clickbait-y such as “Why I No Longer Enjoy Dylan’s Recent Music.” But now that I've got your attention, gather ‘round folks while I tell you a story.

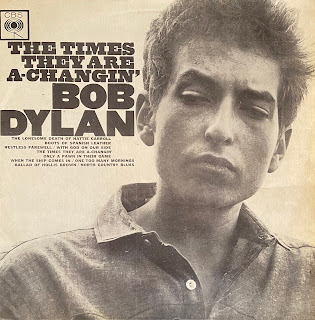

I was just a lad going-on 14 years-old and still in high school when I first discovered Bob Dylan. I’d read about him and seen photos in Record Mirror, then a classmate generously loaned me his copy of The Times They Are A-Changin’ LP and I was hooked right away. The desperately cool image, the powerful songs, the acoustic guitar high in the mix and the voice like sand and glue – it couldn’t have been more perfect. Around the same time Bob appeared on the early evening BBC TV current affairs show Tonight. Introduced by the avuncular Cliff Michelmore he sang “With God On Our Side” and it was, as we would later learn to say, Game Over.

This was May 1964 and, barely a year after the Beatles had won our hearts and our fashion sense, along came Dylan to capture our minds. Together they gave my generation a new way to look and a new way to live. A new way to be, in fact. Between them they became part of the fabric of our lives and took custody of our musical DNA.For reasons unknown, the very first UK Dylan single was “The Times They Are A-Changin’” b/w "Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance" released in March 1965. It was an odd choice as both songs came from albums which were, in those fast ‘n’ furious pop picking times, already considered “old” (Times They Are A-Changin’ and Freewheelin’, respectively).

But Dylan mania was sweeping Britain during 1964/65. In the space of 18 months all six of his LPs released thus far entered the UK top 20, with five of them reaching the top 10 and two (Freewheelin’ and Bringing It All Back Home) peaking at #1. That was Bob’s entire catalogue at that point. In the top 20.

The first Dylan record I bought with my own money (to use that limp cliché) was his fifth LP Bringing It All Back Home in mid-1965. From there I gradually acquired the earlier releases (usually second-hand) while somehow scraping up the cash to buy each new record as it appeared.

This trend continued unabated and uninterrupted for the next 50 years or so. Believe me when I tell you that for five solid decades, I bought absolutely everything concerning Bob I could find: official LP releases (mono and stereo where applicable, naturally), bootlegs, CDs, singles, EPs and compilations (including every one of the cripplingly expensive The Bootleg Series box sets, of which more later), plus books, t-shirts, videos, DVDs and ephemera of all kinds.

At a rough estimate I have well over a hundred Dylan LPs taking up several feet of shelf space on my record racks, plus an equal amount of CDs (following Oh Mercy in 1989 I switched from vinyl to CDs, by necessity, but we won’t go into that). There are multiple copies of most of his 60s LPs, too (eg Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde) because I simply can’t bear to leave them in the shops whenever I see original pressings for sale at an affordable price. They must be originals, though. I can’t be doing with the look, feel or (yes, really) the synthetic smell of today’s overpriced vinyl reissues.

I’ve written reviews and articles about Bob for various record collecting magazines and until recently seldom missed an opportunity to see him in concert. I’ll be the first to admit that I may have taken my Dylan obsession too far at times. So, where did it all go wrong?This may be controversial, but I’m of the opinion that his last great album of new (as opposed to archive) material was the Infidels LP in 1983. It’s a fabulous rock record with top notch songs (“Jokerman,” “Man of Peace,” “License To Kill” etc), a fine band (Mick Taylor, Sly & Robbie, Mark Knopfler) and Bob’s voice is at its early 80s peak. It’s an album where he sings with passion, as if his life depends on it. He belts it out like he really cares. Infidels still gets played regularly around here, although these days it tends to be via the magic of Spotify.

As often happens with Dylan’s records, some great material was left off the released version, including “Blind Willie McTell” and “Foot Of Pride.” Both of these tracks were later mopped up on the first volume of The Bootleg Series in 1991, but there are dozens of other outtakes which will make a great Infidels box set one day.

While on the subject of Infidels it’s worth noting that this perfectly formed album has, somewhat bizarrely, been the subject of controversy in recent years with the tracks “Neighborhood Bully” (pro-Israel), “Union Sundown” (anti-union) and “Sweetheart Like You” (misogyny) singled out for criticism in some quarters. This is ironic considering Bob started his career as the darling of the left-wing protest movement. Iconoclasm is rife today and few of our heroes are immune from its insidious reach. But that’s probably a debate for another time and place.

Infidels was followed by some comparatively low-key records. I’m thinking of Empire Burlesque (1985), Knocked Out Loaded (1986) and Down In The Groove (1988) here. All of them had high points, of course, (eg “Brownsville Girl” on Knocked Out Loaded) but none were what might be called enduring Dylan classics. But the first album which made me question if my relationship with Bob had run its course was Time Out Of Mind in 1997.

Despite some good songs (“Not Dark Yet,” “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven” etc) Daniel Lanois’ swampy, mid-tempo production made many tracks sound alike and I simply couldn’t warm to it. Yet Time Out Of Mind sold very well, won awards and was widely hailed as “a return to form” (another dreadful cliché) by the critics, so what do I know?

The most melodic cut by far was “Make You Feel My Love.” It became a surprise 21st Century classic which has, we are told, already been covered more than 450 times (citation definitely needed here. Ed.) by the likes of Adele, Neil Diamond, Boy George and Bryan Ferry. It subsequently became a popular choice of contestants on those Pop Idol style talent shows where it is invariably performed - melismatic style - by warbling Gen Zers who have, in all probability, never heard of Bob Dylan. And so it goes.

Not everyone agrees with my assessment of this album, clearly. Los Angeles Times music critic and author Robert Hilburn [@roberthilburn] recently said this on Twitter (not my caps): “If Bob Dylan had STARTED his career with Time Out Of Mind and that great string of albums, he STILL would be considered one of America's greatest songwriters.”

By “that great string of albums” Hilburn was presumably referring to Love & Theft (2001), Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009). The first of these includes “Mississippi,” a fabulous song (and a Time Out Of Mind leftover) which came in at #4 in the Rolling Stone list of “The 25 Best Bob Dylan Songs of the 21st Century.” Number one on the list incidentally was “Things Have Changed” a non-album track which earned Bob an Oscar and a Golden Globe when it appeared in the film Wonder Boys. It was a promising start to the new millennium for our man. But then in 2009 came the ludicrous Christmas In The Heart album and things really did begin to change in the Dylan world.

Bob Dylan recording a Christmas record? "WTAF?!?" as I believe the young people say. But those familiar with Bob’s highly entertaining Theme Time Radio Hour* were happy to give him the benefit of the doubt and many assumed he was possibly having a joke with us. Tracks such as “Here Comes Santa Claus” and “Must Be Santa” were, after all, fun and enjoyable in a kitsch, tongue in cheek kind of way. Based on a German polka tune and structured as a boisterous call and response song, “Must Be Santa” was by far the highlight (it even came in at #24 on that Rolling Stone list but, then again, Christmas In The Heart had set a very low bar). But the traditional songs and carols on the album such as “The First Noel” and “O Little Town Of Bethlehem” were much less enjoyable. In fact, most were simply woeful. It was a mighty long way indeed from “Visions Of Johanna.”

With a simple (yet quite delicious) twist of fate, “Must Be Santa” was first recorded in 1960 by the choral group Mitch Miller and the Gang (cover versions by Tommy Steele, Alma Cogan, Joan Regan and others soon followed in Britain). Bandleader and record executive Miller released dozens of huge selling “sing along” choral albums in the 50s and 60s, becoming one of the most influential names in easy listening pop. But in his day job as head of A&R at Columbia records it was Miller who objected most strongly when producer John Hammond brought Dylan to the label in 1961. The painfully un-hip bandleader actively disliked Bob’s singing and he thought that “Hammond’s Folly” (as Dylan became known within the company) was simply not good enough to be given a record deal with Columbia. Miller died in 2010, a year after Christmas In The Heart was released. His views on Bob’s interpretation of “Must Be Santa” are not recorded.

Another hugely significant nail in the coffin was when Dylan gave up playing the guitar. Extensive research (ie two minutes on Google) tells me the last time he played one onstage was 2012, in Chicago. Seeing him perform without a guitar is like seeing Dolly Parton without her wig, Alice Cooper minus make-up or Angus Young devoid of his school uniform. It looks all wrong. Bob’s guitar playing, rudimentary as it may have been in later years, was an essential part of his stage presence and the instrument was inseparable from his image and his music.

It was the late, lamented Jeff Beck who said something like “Hang an electric guitar around the neck of any good-looking kid and he’s instantly a star.” Beck was, in fact, comparing the briefly popular (but subsequently reviled) keyboard guitars, as favoured by jazz/rock fusion players such as Jan Hammer, to traditional electric instruments, but his point was well made. Jeff could well have added: take that guitar away and suddenly the kid is Mel Tormé or Tony Bennett. Or Robbie Williams, if you prefer.

We’re told the reason Bob doesn’t play guitar anymore is due to tendinitis and/or arthritis in both arms making it difficult for him to strum. That’s fair enough, he’s now well into his 80s, for heaven’s sake. But he always has at least two other hotshot guitar slingers in the band taking care of business and his own instrument has been little more than an onstage prop for decades (just as it was with Elvis much of the time). That said, I don’t want to see Bob behind a cheap keyboard on a chrome stand looking like a superannuated member of the Dave Clark Five any more than I want to see him wandering around the stage holding just a microphone, cabaret style.

Following Tempest in 2012, things went from the sublime to the ridiculous with a trio of albums in which Bob groaned his way through five (count 'em) CDs-worth of Sinatra covers and American standards. The first instalment Shadows In The Night (2015) sold well, reaching #1 in the UK and several other countries. This was followed by Fallen Angels (2016) and Triplicate (2017). They didn’t fare quite as well, but both made the charts. And, yes, I foolishly bought them all, including the massively overpriced Triplicate, Bob’s only triple album to date (excluding compilations). Old habits clearly die hard.

He might have got away with releasing one such album, but five discs spread over three albums was stretching the friendship somewhat and hinted at a shortage of new original material. The last time Dylan suffered from an extended bout of writer’s block he gave us the acoustic covers albums Good As I Been To You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993). Although not earth-shattering, both were at least firmly on-brand and Good As I Been To You is worth owning if only for Bob’s gorgeous version of Lonnie Johnson’s “Tomorrow Night.” Incidentally, and somewhat off topic, if you like this kind of thing, check out Bob’s achingly beautiful cover of the 1952 Jo Stafford hit “You Belong To Me” from the 1994 Natural Born Killers movie soundtrack.

Several big-name rock artists have gone down the old standards path, of course, notably Rod Stewart, Paul McCartney and even Ringo. Despite what they may try and tell us, this usually happens when the muse deserts them, and/or new material is proving hard to find. It’s a quick and easy revenue source, after all.

Rod in particular had some of the biggest sellers of his career with the multi volume The Great American Songbook. But it’s a tricky thing to carry off successfully and in my view, only Harry Nilsson managed it with any degree of dignity on his excellent 1973 release A Little Touch Of Schmilsson In The Night. But for me (and plenty of others I’ve spoken to) the stumbling block on all three of the Dylan albums was Bob’s voice.

Ah, yes, let’s talk about Dylan’s voice. It’s a dirty job but someone has to do it. In the 60s our parents tried to tell us he couldn’t sing. That was never true. Not for a second. He didn’t sing like anyone else, perhaps, but his unique vocal style was one of the main things we loved about him. It was powerful, clear and always absolutely in the pocket (as musicians like to say). And, as his voice changed over time we happily went along for the ride. From the hillbilly twang of Freewheelin’, to the amphetamine fuelled nasal whine of Blonde on Blonde. From the silky croon of Nashville Skyline, New Morning and Self Portrait, to the rebel yell of Hard Rain and Rolling Thunder, we lapped it up and came back for more. For 40 years I flew the flag for Bob’s vocals and defended him against detractors every step of the way. If ever there was a hill I was prepared to die on, it would have been this one.

But nothing lasts forever and by the early 2000s Bob’s vocals were no longer the thing of beauty and wonder they had once been. To put it bluntly, his voice seemed virtually ruined. It happens to the best of them as old age creeps up. To some degree or other it’s also happened to Robert Plant, Paul McCartney and Elton John, to name just three of Dylan’s contemporaries. All have lost their range and none of them can project as powerfully as they once did, and we have no right to expect them to. These are men who are a decade or more past pensionable age, after all. But Bob’s voice has suffered more than most. His present-day vocal sound has been called many things, most of them unflattering. “A consumptive death rattle” being just one of the kinder descriptions. His new way of singing alienated many older die-hard fans and, whether they admitted it or not, some young converts found it heavy going, too.

The musical waters became further muddied in the early 2000s as fresh volumes of The Bootleg Series began to appear regularly alongside his new recordings, often causing Dylan overload. The retrospective box sets were uniformly excellent, which often diverted attention from his sometimes-patchy new records. But it was his concert performances which really divided opinion.

Now, I can’t claim to be a regular attendee of The Never Ending Tour but I have seen Dylan play live a dozen or so times, starting with the life-changing 1966 UK tour. I was also at the Isle of Wight in 1969 and the 1978 Earls Court comeback shows. All of them were excellent and important concerts in their own way and I think I can say I’ve seen Bob perform at his peak.

The last concert I attended was 2014 in Perth, Australia. We had front row seats which always improves the concert-going experience, and it was a major thrill to be sitting just a few yards from the man in a smallish (2,500 seat) venue. To paraphrase Bob himself, I was close enough to study the lines on his face, which was worth the price of admission alone.

But, as with all his concerts I’ve seen in the last 20-odd years, musically it was something of a challenge. In fact, the last really great Dylan show for me was the True Confessions Australian tour of 1986 with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers (released on video as Hard To Handle). The band was cooking, Bob’s voice was in great shape, and he chatted freely to the audience, giving rambling introductions and cracking jokes between numbers. Best of all, every song was perfectly recognisable.

Now, I know this is a touchy subject with some Dylan zealots, but it has to be said. I’ve never enjoyed how Bob began mangling his songs around the turn of the millennium. He started changing them almost to the point where (to borrow a line from Alan Partridge) they could be identified only by reference to their dental records or, at best, a few words picked up here and there. I well remember concerts in the early 2000s where fans looked blankly across at each other as yet another unidentified song kicked off. Then someone would recognise a line and hiss “It’s Positively 4th Street” (or whatever it was) along the row and we would all relax until the next number, when the spot the tune game would begin again. Some of the lofty excuses offered were “They’re his songs, so he can sing them how he wants,” or “The songs are not set in stone, they’re organic.” But I’ve never subscribed to that view.

In moderation this technique can sometimes prove interesting, admittedly. The version of “Like A Rolling Stone” on the Bob Dylan At Budokan 1979 live album is a case in point. The backing is stripped back and the chord sequence is markedly different to the original (some chords are missing, although perhaps only a musician would notice this), giving the song a more urgent feel, which works perfectly. 20 years later Bob would take these rearrangements to undreamed of (some might say ridiculous) extremes.

Then there was the hit and miss nature of the performances themselves. Whenever I expressed disappointment with a Dylan concert, I was often blithely told “Oh, you must have seen a bad show, but every now and then Bob will perform the best concert ever. Three nights later in Dublin (or wherever) the show was especially good. You just have to be lucky and catch him on a good night.” Well, excuse me, but the thought of paying hundreds of dollars for tickets with the slim chance that I might “get lucky” and see him deliver a decent show no longer seems particularly appealing. In fact, it turns the audience/performer dynamic on its head.

And yet, every time a new leg of The Never-Ending Tour kicks off, we see a tsunami of superlatives from fans on Twitter proclaiming they've witnessed the best concert in the history of the world, by anyone, ever. Inevitably, a few devotees even claim to have invested their life savings flying from city to city to attend every show in North America and Europe (how’s your carbon footprint, guys?) It’s almost as if they consider the Dylan tours to be like visiting a famous museum or art gallery which they can then tick off their bucket list. Others appear to view their attendance as an act of ecumenical worship. For some, Dylan’s concerts have now become analogous to religious gatherings it seems.

In the final analysis it’s all a matter of personal taste of course. Bob Dylan is no longer the same performer whose music we thrilled to 40 or 50 years ago. His most recent studio album Rough and Rowdy Ways arrived unannounced in 2020 preceded by the extraordinary 17 minute spoken poem “Murder Most Foul” (#5 in the Rolling Stone list). Although I couldn’t decide if he was celebrating or mocking the Fab Four with the line “The Beatles are comin’, they’re gonna hold your hand,” it was nevertheless a thrill to hear him name-check them in a song. It seemed we had gone full circle and arrived back to 1964.

But no matter how good, bad or downright bizarre the albums and the live performances, the weight of his legend and the importance of his massive back catalogue will always carry him through. Such is Dylan’s cultural significance - his brand recognition if you like - he has become almost a mythical figure for many, especially among those who weren’t around to see him play live in the 60s (ie most people).

As of 2023, Bob has been performing and making records for more than 60 years. It’s been said he keeps touring because he doesn’t know how to stop. But how much longer can he continue before he has to stop? Another five years perhaps? He’ll be 87 by then and we’ll be sailing deep into uncharted waters with a strong following wind. Few, if any, artists in rock have ever maintained a career for that long.

It goes without saying that I’ll always listen to Dylan’s early records. At least, all those where his voice was still in good shape, plus the seemingly endless supply of The Bootleg Series retrospectives as well. Yes, the first 27 years of his catalogue (up to and including 1989's Oh Mercy) will do me just fine, thanks.

I like to think Bob’s music has always given more than it took from me, but the gap has narrowed considerably in recent years and I’m fast running out of stamina. Thanks Bob, it’s been a long, strange trip. And, like I said, it’s not you, it’s me. Or, as an old girlfriend once quipped before flouncing out the door for the final time “I’m not incompatible, you are.”

Thanks to: Dylan writer and Twitter hound Roy Kelly for his encouragement and inspiration. Find Roy on Twitter @stanyanfan49