by Stuart Penney

I first became aware of Jimi Hendrix around Christmas of 1966 when “Hey Joe” burst through the tiny (not to say tinny) speakers of our transistor radios. The BBC’s lone pop station Radio 1 was still almost a year away, so most people encountered Jimi’s debut single via the faint, unpredictable signal from Radio Luxembourg, or perhaps one of the maverick pirate stations such as Radio Caroline or Radio London. Chas Chandler, the Animals’ bassist, had brought Hendrix over from New York on September 24 and within weeks he was playing warm-up shows around the trendy London clubs with the hastily assembled Experience to widespread dismay from every hot shot guitar slinger in town.

The rest of the population had to wait until December to meet Jimi when he appeared on national TV playing “Hey Joe” live on Ready Steady Go! Parents were appalled at the sight of him, naturally, and the newspapers made no attempt to disguise their disgust or their casual racism. I think it was the Daily Mirror who first referred to Hendrix as “The Wild Man of Borneo”, but they were by no means alone in employing this kind of crude rhetoric and the same ugly epithet even appeared in some corners of the music press, notably Disc & Music Echo. The truth was the mainstream media simply had no idea what to make of a black man who looked this sensational and behaved so outrageously.

The kids loved him right away, of course. The newly fashionable military hussar jackets, the brightly coloured satin and silk outfits, the high-heeled boots, the halo of wild hair and, best of all, the Fender Stratocaster flipped upside-down for the left-handed Jimi. It was all so new, different and exciting. If Eric Clapton, then riding high with Cream, was considered “God” by the young white rock fans, then Jimi would soon be regarded as an altogether more colourful and enigmatic kind of deity – the multi-armed Vishnu, perhaps, as later depicted on the cover of his second album Axis: Bold As Love.

Listening to “Hey Joe” today, you wonder what all the fuss was about. It was a great pop single, to be sure, but it no longer appears particularly wild or shocking, especially when compared to much of Jimi’s later work. An old-style murder ballad with repeated verses, it has no middle eight or bridge, but a concise and beautifully phrased eight bar guitar solo recorded at reasonably low volume with a clean, undistorted tone. The song is taken at a leisurely pace with a chord sequence (C,G,D,A,E) which could have come straight from a folk tune and there are even female backing vocals, courtesy of The Breakaways, who supply the breathy “ooh-aah” accompaniment.

But the impact of the record in 1966 was seismic. Appearing on Top Of The Pops and other TV shows Hendrix seemed other-worldly, playing the guitar behind his head, between his legs, with his teeth and employing all the onstage tricks which would soon become familiar. Like almost everyone else of my generation, I was mesmerised by him and devoured every scrap of information, photograph and news cutting I could find. And then in early 1967 it was announced that Jimi would be playing live just 10 miles away in Chesterfield. This I had to see.

ABC Cinema, Cavendish Street, Chesterfield - Saturday April 8, 1967

Throughout the 50s and 60s multi artist package tours were the most popular way of presenting live pop music in Britain, particularly in the towns outside London. Travelling up and down the country and stopping off in a different city every night, the tours usually featured five or six groups or solo artists, each playing sets of around 20-30 minutes, generally consisting of their current hit single, plus a handful of other favourites. With so many acts on the bill the audience scarcely had time to get bored. If you didn’t like a particular artist, no problem, another one would be along in a few minutes.

With an average seating capacity of around 2,000, cinemas were the perfect venues to host the package tours and most towns and cities utilised them in this way, alternating one-night stand live concerts with the films of the day. But by the late 60s the package tours started to wind down as the new rock era ushered in a different style of music which didn’t fit the traditional show biz model at all. The arrival of the multiplex cinema was another factor in their demise.

While a few larger London cinemas such as the Hammersmith Odeon and the Finsbury Park Astoria eventually dropped films altogether to become full-time concert venues in the 70s they were the exception. Out in the provinces the move to smaller, multi-screen cinemas in the late 60s not only sealed their fate as live music venues but effectively killed the package tour circuit as well.

Although not exactly thriving, the package tours were still around as we entered the Summer of Love, and on April 8, 1967 I found myself at the ABC Cinema in Chesterfield to witness one of the most unlikely collection of artists ever to share a stage. After brief sets by the two anonymous support bands The Californians and The Quotations, Cat Stevens got the main show underway. Then just three Deram singles into his short pop career with “I Love My Dog”, “Matthew and Son” and his then-current hit “I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun”, Cat performed part of his set in a cowboy hat, brandishing a fake revolver. By 1970 he would leave the pop world behind to become a successful singer-songwriter with big-selling albums for Island, such as Tea For The Tillerman and Teaser and the Firecat.

|

| Tour Programme 1 |

Next up was Engelbert Humperdinck who closed the first half* with “Release Me”, his debut single under his new identity (he had earlier recorded as Gerry Dorsey, a variation of his real name). “Release Me” was a colossal hit and will forever be remembered as the record that ended the Beatles’ run of 11 straight UK number ones, preventing “Strawberry Fields Forever” / “Penny Lane” from reaching the top spot, for which some of us have never quite forgiven Engelbert. Undaunted, the Fab Four went on to have six more UK chart toppers.

*Other dates on the tour had a slightly different running order with Jimi and Cat Stevens sometimes exchanging places on the bill.

Hendrix opened the second half in fine style. His second single “Purple Haze” had been released just weeks earlier on March 17 and while his debut album Are You Experienced was still a couple of months away, two top ten hit singles were enough to justify his mid-bill position on the tour. Jimi’s brief set was: “Foxy Lady”, “Can You See Me”, “Hey Joe”, “Purple Haze” and “Fire”.

|

| Tour Programme 2 |

While the careers of Cat, Jimi and Engelbert were very much in the ascendant the Walkers had already reached their peak and would effectively disband immediately after this tour. In fact they scored only one further UK top 30 hit in the 60s before managing a brief comeback with “No Regrets” in 1976.

After Engelbert’s set many of the older audience members (who we snootily referred to as “the civilians”) got up to leave during the interval, never to return, leaving entire rows of seats empty when the second half began. Perhaps they had read reports of Jimi’s antics on the first night of the tour in London where he famously set fire to his guitar, creating cultural shockwaves around the world.

Chesterfield was the seventh show of a 25 date UK tour which began and ended in London. Kicking off on the last day of March 1967 at the Finsbury Park Astoria (later to be re-branded as the Rainbow), the tour ran for exactly one month, ending at the Granada cinema in Tooting on April 30. Package tours generally played twice nightly, with a matinee performance around 6pm, followed by the main show at 8.30pm or later, so there were actually 50 shows in total. Ticket prices at Chesterfield ranged from 7s/6d (37½p) to 15 shillings (75p).

Completing the bill were The Californians, a surf outfit from Wolverhampton who played a 10-minute spot. The Quotations opened both halves of the show with their own short set before backing the Walkers and Cat Stevens.

Chesterfield Trivia:

According to a report in Disc & Music Echo (15th April, 1967 issue), Jimi required four stitches in his foot after a “fuzz-box incident” during the early Chesterfield show “but he was able to go on for the second house.”

We didn’t know it at the time, but Engelbert’s guitarist left the tour after just a few shows and Noel Redding was reportedly hired to replace him, for which he was paid an extra £2 per night. Originally a guitarist before joining the Experience on bass, Redding would stand in the wings playing guitar with a very long lead while Engelbert was on stage (they wouldn’t let him appear on stage with the other band members). Noel later said, "I wonder if anyone in the audience ever guessed where the lead guitar was coming from?" Engelbert has since claimed that it was, in fact, Jimi and not Noel who deputised for his missing guitarist. This makes for a better story, but it's probably not true.

The 2,000 seat ABC Cinema in Chesterfield opened in 1936 as “The Regal” and was re-named the ABC in 1961. It was converted to a smaller multiplex cinema in 1971 and eventually closed in 1998. The building was then used as a series of nightclubs until 2014. The ground floor is currently occupied by Boyes department store, while the upstairs circle remains empty.

Barbeque 67 - The Tulip Bulb Auction Hall, Spalding, May 29, 1967

Flowers are big business in the East Midlands county of Lincolnshire and not for nothing is the area around Spalding known as South Holland. Between 1959 and 2013 the town even held an annual flower parade celebrating the region’s vast tulip production and its cultural links with Holland. And so, on May 29, just seven weeks after the Chesterfield concert, I arrived at the wonderfully named Tulip Bulb Auction Hall in Spalding to witness an entirely different kind of show. The name sounds romantic but in reality the venue resembled an oversized cattle shed with, as I would later discover, a cold, unforgiving concrete floor.

I’d hitchhiked the 90 miles from Sheffield with Alan, a pal from college and since this was a bank holiday Monday with not much commercial traffic around, the journey took hours longer than expected.

If the Chesterfield line-up was bizarre, then the all-day show at Spalding was the stuff of dreams, especially when viewed at this distance. Appearing that momentous day, in vague order of appearance, was: Zoot Money and his Big Roll Band, The Move, Pink Floyd, Geno Washington and the Ram Jam Band, Cream and topping the bill, the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Local outfit Sounds Force 5 played during the main band changeovers. Did I mention the tickets cost just one pound? That converts to a little over £18 today, which is still an unbelievable bargain.

“Non-stop dancing 4pm to Midnight” boasted the Barbeque 67 posters, with echoes of an bygone era. Had there been any room to move I suppose dancing to the soul / R&B beat of Geno Washington and Zoot Money might have been theoretically possible. But with (reportedly) 6,000 fans packed into the hall, were the promoters really expecting people to bop along to the freak out sounds of Floyd, Cream and Hendrix? Surely not. But let’s not forget, this was one of the earliest events of its kind, before Monterey, before any of the Isle of Wight festivals and certainly before Woodstock or Glastonbury. No wonder the organisers were making up the rules as they went along.

As for Pink Floyd, they were a fairly new band with just one single, “Arnold Layne”, to their name in May 1967. Their second 45 “See Emily Play” was still two weeks away and their debut LP Piper At The Gates Of Dawn wouldn’t be released until early August. While we were waiting for the venue doors to open I took a walk around the building and encountered Floyd drummer Nick Mason in the car park. He was sitting in the open boot of a Ford Zodiac MK III (a fairly upmarket car at the time) wearing a distinctive bright yellow Afghan coat. This garment crops up in many Pink Floyd photos from 1967 and can be seen draped over Nick’s drum stool in the onstage pictures from Spalding. This was prime Syd Barratt-era Floyd, but as they were virtual unknowns at that time, especially outside London, few people walking though the car park knew, or much cared, who they were.

|

| Pink Floyd in action at Spalding |

The Move were another band enjoying the first flush of success and in early 1967 they had released only two singles for Deram, the excellent “Night Of Fear” and “I Can Hear The Grass Grow”. Both had been UK top five hits, but a switch to the Regal Zonophone label in August would prove even more fruitful, producing “Flowers In The Rain” and several other great pop psych hits. Roy Wood memorably played a 12-string Fender Electric XII guitar on the night.

Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band were within weeks of morphing into the short-lived psych outfit Dantalian's Chariot and the man himself was already wearing a suitably gaudy floral jacket. But musically it was business as usual with “Big Time Operator” and other R&B classics. Zany as always, Zoot may even have dropped his trousers mid-song at Spalding, as was his onstage habit at that time (I guess you had to be there). The band timeline tells us that future Police man Andy Summers was playing guitar in the Big Roll Band at that point, but I can’t swear to it.

It was a surprise to see Cream surrender top billing to Hendrix, but the Experience sales figures were already outstripping those of Eric, Jack and Ginger and so Jimi was presumably seen as the bigger act on the day. Hendrix and Cream each had just one album in the shops at that point (Are You Experienced had been released only 17 days earlier, while Fresh Cream appeared back in December 1966) and while both LPs sold well, Jimi’s three top 10 singles to date (“Hey Joe”, “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary”) had outsold Cream’s disappointing “Wrapping Paper” and “I Feel Free”, so he had the all-important chart placings in his favour.

But it’s generally accepted that Cream won the day with a tight, powerful set and the Spalding bootlegs seem to confirm this. Several unauthorised recordings have surfaced over the years and while many are appropriately titled Tulip Bulb Auction Hall after the venue, the covers invariably show pictures of the band performing elsewhere, usually on a flatbed truck in Copenhagen almost a year later. At Barbeque 67 Eric played his legendary hand-painted 1964 Gibson SG Standard dubbed “The Fool”, while Jack Bruce used a Danelectro Longhorn bass. This was also our first sighting of Clapton's Hendrix-inspired perm.

Cream's set list: NSU / Sunshine Of Your Love / We're Going Wrong / Steppin' Out / Rollin' & Tumblin' / Toad / I'm So Glad.

Then it was Jimi’s turn. “It’s just like Hank Marvin’s”, was my first thought as Hendrix took the stage with a Fiesta Red Fender Stratocaster. That’s where any similarity with the Shadows’ bespectacled leader ended, however. Always the embodiment of cool, Jimi was wearing a flamboyant drape jacket with a metallic paisley design and brightly striped trousers. The jacket was soon abandoned to reveal an embroidered velvet waistcoat over a white blouse with huge lace ruffles down the front and on the cuffs. Noel and Mitch were just as colourfully kitted out and the drummer now had a perm, so all three band members sported impressive afro hairstyles.

The Experience were late arriving onstage and encountered sound problems from the start. Jimi was clearly having difficulty staying in tune and the red Stratocaster was eventually sacrificed, ending up in pieces. Some reports say he set it alight, but I don’t remember that, and I was only standing around 20 feet from the stage, pressed tight up against the right-hand wall. Jimi’s exact set list is undocumented, but I do recall “Foxy Lady”, “Hey Joe”, “The Wind Cries Mary” and, best of all, a version of Dylan’s “Like A Rolling Stone” which would go down so well at the Monterey Pop Festival just 20 days later. History has not been particularly kind to the Experience’s performance at Spalding with some describing their set as “a shambles”, or worse. But as a 16 year-old I cared little for any of that. I was thrilled beyond words just to be there watching Jimi perform and breathing the same air as the man.

After the show we were allowed to sleep overnight in the hall. Typically ill-prepared, we hadn’t brought sleeping bags or even a blanket, so spent a long, uncomfortable night on the cold concrete floor using our rolled-up coats as pillows. Jimi, meanwhile, slept more comfortably at the local Red Lion Hotel where, in 2015, a blue plaque was erected to commemorate his visit to the town.

The Barbeque 67 promoters fully intended to repeat the event the following year but following objections from Spalding residents it was moved 20 miles away to the small town of Whittlesey in Cambridgeshire. The 1968 festival, titled Barn Barbeque Concert and Dance, was held over the Whitsun weekend of June 2 and 3 and featured Donovan, Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, Fairport Convention, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and many others. Yes, I was there too.

Saville Theatre, London - August 27, 1967

Back in the good old pre-pandemic days when the West End was thriving, it was a long-standing tradition that most London theatres remained “dark” (ie closed) on Sundays, presumably to give the actors and crew a rest day. In April 1965 Brian Epstein took over the lease on the Saville theatre down at the unfashionable end of Shaftesbury Avenue and since the place was sitting empty he came up with the brilliant idea of presenting Sunday night rock concerts there. Jimi played the Saville a total of five times, starting on January 29, 1967 supporting the Who. Two days later he also filmed a promo clip there, miming to “Hey Joe”.

By mid-1967 I was living in London and soon became a semi-regular at these Sunday shows. It seems incredible now that bands as important as Cream, Hendrix and the Who played shows in London almost weekly in the 60s and it was nearly always possible to get tickets to see even the biggest names. These were the days of massive record sales and while concerts were popular (and cheap), live music came a poor second in terms of earned income for the musicians. Of course, the reverse is true today.

Hendrix had been out of the country for a couple of months, so when it was announced that he was booked to play the Saville on August 27 with support by the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Tomorrow (featuring Keith West and Steve Howe), I simply walked to the theatre box office in my lunch break and snapped up a ticket right away.

This story ends badly, unfortunately. Arriving at the Saville on the night I was met with an A-frame (or, as it was then called, a sandwich board) sitting out on the pavement with a sign reading something to the effect of “Due to the death of Mr. Brian Epstein, tonight’s concert by Jimi Hendrix has been cancelled”. It was customary to have two shows a night back then and while the early concert had gone ahead as planned, it was decided to call off the second show as the news of Brian’s death began to filter through.

As we “heads” might well have said at the time - bummer! Major bummer, in fact. I was sad we’d lost Brian, of course I was, but missing out on a Hendrix concert seemed almost as devastating at the time.

I have no recollection of getting a ticket refund or an exchange, but something of the sort must have happened because five weeks later I was back at the Saville to try again.

Saville Theatre, London - October 8, 1967

The show must go on and The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown was brought back as Jimi’s main support act for the October 8 Saville performance. There is some confusion as to who else was on the bill, however. The concert programme lists Irish band Eire Apparent (featuring Henry McCullough and Ernie Graham) and The Herd (with Peter Frampton), while advertisements in International Times claim it was John’s Children (post Marc Bolan) and the Crying Shames (probably a misspelling of the Decca band Cryin’ Shames). I was there but have no memory of the support bands other than Arthur Brown with his distinctive face paint and (quite possibly life-threatening) flaming helmet.

I do remember that Noel Redding used a seldom-seen Fender Bass V in Lake Placid Blue for this show. A rare and unusual five string instrument with only 15 frets (but a fairly standard Fender 34" scale), it was in production for just six years, between 1965 - 1971. The only other Bass V player of note I’m aware of is John Paul Jones in Led Zeppelin.

As for Jimi, he was perhaps the only guitar hero who didn’t seem to have an affinity with one particular guitar. Sure, he favoured Fender Stratocasters during most of his career, but seemingly used a different instrument almost every week. It appears his Strats were bought new (or sometimes second-hand), off the peg, in a range of colours at one of the London guitar stores and played to destruction after just a few shows. A Fender Stratocaster cost roughly £250* in 1967, equivalent to over £4,500 in 2020, so in real terms they were more expensive back then than now. And that figure doesn’t include all those damaged Marshall amplifiers, torn speaker cabinets and crushed effects pedals.

*That was the price of a new guitar. Melody Maker ads of the mid to late 60s confirm that second-hand Stratocasters were available for around £100.

Someone must have pointed out the economic facts of life to Jimi this night because as he came out for the encore on October 8 (the point in the night where his guitar usually met its demise) he was carrying not the white Stratocaster he had tortured during the main part of the show, but a smaller guitar, which at the time I guessed was a Fender Mustang*. These were cheaper, so-called “student” instruments, costing less than half as much as a Stratocaster and used examples could be picked up for around £80 at one of the Charing Cross Road music stores at that time.

*The jury is still out on exactly which guitar Jimi used for the encore. From a few rows back, it was difficult to pinpoint the model. If not a Fender Mustang it could have been one of the other Fender small body guitars such as a Duo-Sonic, Musicmaster or Bronco, all of which are visually very similar from a distance.

Inevitably, the new instrument ended up in pieces, after which Hendrix threw it behind the Marshall stacks, but I often wonder if the Track accountants had told Jimi to lighten up on his guitar expenditure for that week. Most people wouldn’t notice such a thing, but Team Hendrix clearly hadn’t bargained on the sharp-eyed guitar nerds in the audience. I’ve no idea if this cost cutting measure was a one-off event, but I’ve never seen any photographic evidence of Jimi using a “stand-in” guitar like this again.

Another unforgettable moment came right at the end as Jimi began to bump and grind the encore guitar up against the wall of amps during the final song, “Wild Thing”. With no regard for personal safety, a brave roadie threw his entire weight against the massive stacks from behind, attempting to prevent the double speaker cabinets from toppling over backwards as Hendrix slammed the guitar - and his body - into them, to the accompaniment of howling feedback. Most in the audience didn’t see this drama unfold but those of us positioned off to the side witnessed the entire spectacle.

A month later on November 10, 1967 The Beatles shot the promo film for "Hello, Goodbye" on the Saville theatre stage. The building is still operating today as a cinema, renamed the Odeon Covent Garden.

Saville Theatre Set list:

- The Wind Cries Mary

- The Burning Of The Midnight Lamp

- Hound Dog

- Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?

- Hoochie Coochie Man/Drum Solo

- Purple Haze

- Foxy Lady

- Wild Thing

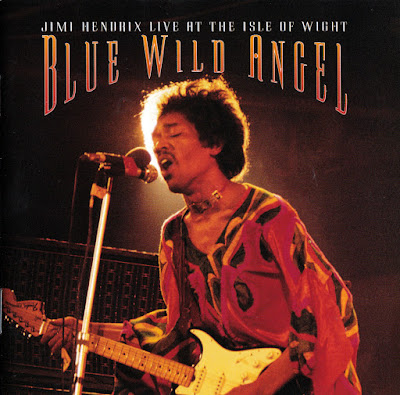

Isle of Wight Festival, East Afton Farm, Freshwater - August 30, 1970

Back at the microphone Jimi continues “You can join in and start singing. Matter of fact it’ll sound better if you’d stand up for your country and your beliefs and start singing. And if you don’t…. fuck ya.” The trio then launch into a feedback-drenched version of the national anthem. And so began Jimi’s last-ever live show in Britain.

We know all this, and a great deal more besides because, along with his appearances at Woodstock and Monterey, Jimi’s every last utterance at the Isle of Wight has been precisely documented on records, CDs, DVDs, films, books and glossy magazines and the actual performance needs little further description here.

To recap. Almost three years had passed since I’d last seen Hendrix play. Since then he’d spent most of his time back in America, making occasional forays into mainland Europe and playing only a handful of UK dates. The magnificent Axis: Bold As Love and Electric Ladyland albums arrived in 1967 and 1968 respectively, while the short-lived Band of Gypsys came and went at the end of 1969. Noel Redding had been replaced on bass by Jimi’s army buddy Billy Cox, and Mitch Mitchell was back in the fold after an enforced absence. So, when it was announced this trio was to headline the 1970 Isle of Wight festival it was a huge deal, on the same level as Bob Dylan’s comeback appearance at the 1969 event.

But what of the festival itself? Reaching the Isle Of Wight was no easy task. Firstly, it required a 75-mile trek from London to Portsmouth down on the south coast (reached by hitching, as usual). From there a 25-minute ferry journey across the choppy Solent took us to the island, followed by an uncomfortable 30-minute ride in a ramshackle, overcrowded bus hurtling, with scant regard for the speed limit, along narrow country lanes to the festival site 18 miles away. None of this includes time spent waiting in line - and with an estimated 600,000 festival attendees (on an island with a resident population of just 100,000) there was a great deal of queuing involved at virtually every step of the way.

After disembarking the ferry at the port of Ryde (cue endless Ticket To Ryde gags - hilarious at the time, believe me), we were met at the quay by teams of Hampshire’s Finest, intent on making arrests. In late 60s Britain possession of the smallest amount of marijuana could land you in jail and the longhairs flooding in from the mainland represented easy pickings for the police. The 1970 IOW festival may have rivalled Woodstock in size, but news of the Aquarian Age was yet to reach an island which was still firmly stuck in the 1950s.

The undercover cops had gone to considerable effort to merge with the festival goers and they were wearing what they laughably imagined to be hippy gear, consisting of cheap Woolworths brand jeans, headbands and nondescript white t-shirts. In a gauche attempt to blend in, some of the female officers had taken to wearing their regulation police issue blouses tied up in a knot at the front, exposing a generous amount of bare midriff. Even so, the shiny black shoes and severe haircuts (on the male officers, at least), identified them as police at a glance.

Inevitably, my girlfriend and I were pulled from the queue and searched. The police got quite excited when they discovered a silver foil package in my backpack, and we were taken to a nearby caravan for further grilling. We were soon released, however, when the red-faced cops realised the package contained nothing more harmful than a black pudding sausage (a Yorkshire delicacy, don’t ask) thoughtfully supplied by my girlfriend’s mother. Being British police, of course, they bumbled their way politely through the entire process and I can’t say we ever felt particularly intimidated.

The 1970 festival is said to be one of the largest events in rock history. Possibly even bigger than Woodstock (it included eight acts who had also appeared there) with a more impressive and varied line-up. Having been to the smaller 1969 IOW festival I knew the level of discomfort involved. But with four times as many people trying to reach the island this time the 1970 gathering proved to be an endurance test of epic proportions.

The weather was uncomfortably hot and humid that year and, since shorts were definitely not yet considered a fashion option for the image-conscious UK rock fan, there was no respite from the heat. On-site food was expensive, of variable quality and, like everything else, involved endless queuing. As for the toilets, they were nightmarish, foul-smelling rows of open trenches, screened by tarpaulin covered scaffolding and you simply didn’t use them unless you absolutely had to.

Weekend ticket prices for the three main days of the festival cost £3, which converts to around £47 in 2020, still an absurdly small amount of money for the phenomenal array of world class talent on offer. We turned up without tickets, however, intending to purchase them on arrival (you could do that kind of thing back then). But, after a quick assessment of the site layout, our strategy changed. To the left of the stage, beyond the fence, was a 200 foot (61m) high escarpment dubbed Devastation Hill. This steep incline offered an unobstructed (if somewhat distant) view of the performers and, what’s more, it was free!

|

| The view from Devastation Hill |

This was just one aspect of the unpleasantness that unfolded at the festival and we witnessed several ugly clashes of ideology. On one side were the French and German anarchists, intent on tearing down the fences while insisting that all music (and probably everything else) should be made free. On the other were the capitalist breadhead festival organisers, supposedly ripping off the kids (and the bands, too, for all we knew). As Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson later recalled “I think it was a defining moment in that change from the hippy ideals to the rather dark and pragmatic side of music.”

After being jeered off during the first of his two sets, Kris Kristofferson took a more jaundiced view. "It was a total disaster," he remembered. "They just hated us. They hated everything. They booed us, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, Sly Stone; they threw shit at Jimi Hendrix. At the end of the night, they were tearing down the outer walls, setting fire to the concessions, burning their tents, shouting obscenities. Peace and love it was not."

With so many acts on the bill it wasn’t possible to catch everyone on our “must see” list, but we gave it our best shot, starting with local heroes from our Ladbroke Grove neighbourhood, Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies. They played for free (of course they did) beyond the fences in front of the inflatable Canvas City tent (and probably inside it as well). On the main stage we saw Free, Joni Mitchell, The Who, Ten Years After, Pentangle, Jethro Tull, Donovan, Taste (with Rory Gallagher) and of course Hendrix. With the possible exception of TYA, I think it’s fair to say that the music every one of those artists made back then remains just as relevant and life-affirming today as it was half a century ago. Make of that what you will.

But for many who made the Isle of Wight pilgrimage it was all about Jimi. Regrettably, his set was plagued by technical problems (during "Machine Gun" the security personnel's walkie-talkie radio was clearly heard through the guitar amplifiers), which, combined with the late hour, didn’t make for a vintage performance. We might have been more concerned had we known this was the last time we would ever see him perform. By the time Hendrix took the stage in the early hours of Monday the event had been underway for more than 72 hours. With festival fatigue setting in, many fans were already drifting back to the ferries looking to make an early getaway.

It’s often assumed that Hendrix closed the festival but in fact he was followed by Joan Baez and Leonard Cohen who played well into Monday morning. Richie Havens eventually brought proceedings to a fitting conclusion at daybreak with “Freedom”, one of the first songs to be heard at Woodstock a year earlier.

The 1970 festival was declared a free event on the final day and so ended as a commercial (but certainly not artistic) failure. Long-standing hostility to the event by Isle of Wight residents resulted in an act of parliament blocking similar large gatherings on the island, meaning that no further festivals took place there for more than 30 years.

A posthumous Hendrix LP titled Isle Of Wight containing just part of Jimi’s set was released in November 1971. For reasons unknown the cover photo they used was not taken at the IOW, but from a September 4, 1970 concert at Deutschlandhalle, Berlin, two days before his last-ever show.

Jimi Hendrix Set List - Isle of Wight 1970

|

| 2002 CD with full IOW set |

- God Save the Queen

- Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

- Spanish Castle Magic

- All Along the Watchtower

- Machine Gun

- Lover Man

- Freedom

- Red House

- Dolly Dagger

- Midnight Lightning

- Foxy Lady

- Message of Love

- Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)

- Ezy Ryder

- Hey Joe

- Purple Haze

- Voodoo Child (Slight Return)

- In From the Storm

Artist Line-Up - Isle of Wight 1970

Wednesday 26th August: Judas Jump, Kathy Smith, Rosalie Sorrels with David Bromberg, Kris Kristofferson (first set), Mighty Baby.

Thursday 27th August: Gary Farr, Supertramp, Andy Roberts & Everyone, Ray Owen, Howl (featuring Frankie Miller), Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, Black Widow, Groundhogs, Terry Reid, Gracious!

Friday 28th August: Fairfield Parlour, Arrival, Lighthouse, Taste, Tony Joe White, Chicago, Family, Procol Harum, The Voices Of East Harlem, Cactus.

Saturday 29th August: John Sebastian, Shawn Philips, Lighthouse, Mungo Jerry (didn’t perform), Joni Mitchell, Tiny Tim, Miles Davis, Ten Years After, Emerson Lake & Palmer, The Doors, The Who, Melanie, Sly & the Family Stone.

Sunday 30th August: Good News, Kris Kristofferson (second set), Ralph McTell, Heaven, Free, Donovan & Open Road, Pentangle, The Moody Blues, Jethro Tull, Jimi Hendrix, Joan Baez, Leonard Cohen, Richie Havens.

Canvas City Performances

Hawkwind

Pink Fairies

Notting Hill Gate - September 18, 1970

Immediately after the Isle of Wight, Jimi played a handful of European dates, culminating in his last-ever show on September 6 at the ill-fated Open Air Love and Peace festival on the Baltic island of Fehmarn, Germany. Despite an impressive bill which included Alexis Korner, Ginger Baker’s Airforce, Fotheringay, Canned Heat, the Faces, Mungo Jerry and Sly & the Family Stone the festival was a disaster, not least because of some terrible weather and an unwelcome visit from the German Hells Angels. Back in London on September 16 he appeared onstage for the final time jamming with Eric Burdon and War at Ronnie Scott’s club. We didn’t know much of this at the time, of course, and wouldn’t learn the full details until the history books started to be written.

|

| Electric Ladyland - Original UK Cover |

50 years on, Jimi’s legend has grown way beyond anything we could have foreseen in 1970. In a world of downloads and streaming, his music sells better than it did when he was alive. He inhabits all aspects of the lucrative rock nostalgia market and hardly a month goes by when his face doesn’t appear on the cover of Mojo, Uncut, Classic Rock or one of the other so-called dad rock monthlies where men of a certain age gather to reminisce and where the 60s reign supreme. It’s a similar story in the guitar world where the magazines are more technically inclined and generally attract a younger readership. But even here among the academy trained shredders Hendrix’s unique guitar style is still revered and his outrageous virtuosity and timeless image speak loudly to every generation. He may have burned brightly for less than four years in the late 60s, but the man and his music remain eternally relevant.

It’s been said that Jimi’s legacy has been diluted, not to say milked dry, by the seemingly endless flow of material released since his death, much of it substandard leftover tracks or so-so live recordings. Musically speaking, the custodians of his estate reached the bottom of Jimi's barrel a long time ago. Undaunted, they have continued digging, seemingly setting a course for the Earth’s core. There’s a cruel jibe that sums up the Hendrix catalogue as: “Four stupendous albums when he was alive and 40 terrible ones since he died.” That’s stretching the truth, perhaps, but not by very much. There have been some genuinely great posthumous releases, admittedly, but very few of them have come even close to matching the four perfect records Jimi lived to see released: Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love, Electric Ladyland and Band Of Gypsys. But when all is said and done, how could they?

Fantastic piece, Stuart!

ReplyDeleteThank you, sir. Very kind

DeleteGreat article! Loved it!

ReplyDeleteA,mother cracking article, loved it. I remember seeing Mungo Jerry at Beatty Park Pool (a support I think) and towards the end of the set Reg started playing with a cheap looking acoustic and then proceeded to smash it…an even cheaper option!

ReplyDeleteA,mother…ffs…Another

ReplyDeleteThank you for writing this article. Wonderful stuff, great memories, an extraordinary artist. I'm writing my own Hendrix piece, an odd story about a Hendrix museum in Vancouver, lovingly crafted, obviously a bit naff, now long gone like so many old forgotten city streets. Cheers

ReplyDeleteMany thanks and best of luck with own Hendrix piece

DeleteExcellent as usual. A legitimate archival document of record. Maybe a piece on the post death releases some time.

ReplyDeleteGreat write up 👍 Oh, and I'm jealous but I was only 5 in '67.

ReplyDeleteNoel Redding's story about playing stand-in guitar for Engelbert could well be a lie. He was always bigging-up his role in the Experience.

ReplyDeleteCan I direct Hendrix fans to deadhendrix.blogspot.com? Thank 'ee!

Could be, but then Engelbert later upped the ante and claimed it was Jimi who was the stand-in guitarist

DeleteI was at the Saville for the rescheduled gig following the death of Brian Epstein. The Herd were definitely on bill that night. Peter Frampton threw bananas into the stalls at the end of their set. I also recall an incident during the Hendrix set when the lead came out of his guitar and he rushed across the stage and pulled out Noel Reddings lead and plugged it into his strat. Roadies certainly earned their bread that night.

ReplyDeleteThaks for that, nice to get the facts from someone else who was there!

Delete